DNA origami

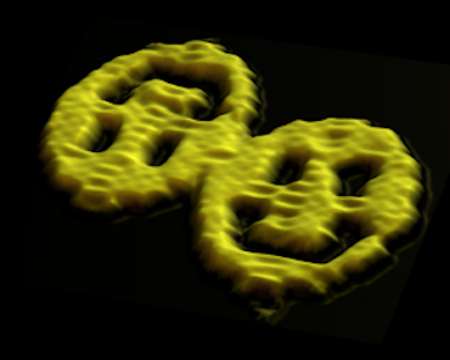

In 2006, I reported a method of creating nanoscale shapes and patterns using DNA. Each of the two smiley faces above are actually giant DNA complexes imaged with an atomic force microscope. Each is about 100 nanometers across (1/1000th the width of a human hair), 2 nanometers thick, and each is comprised of about 14,000 DNA bases. 7000 of these DNA bases belong to a long single strand, a DNA molecule that just happens to be the genome of the virus M13. The other 7000 of these bases belong to about 250 shorter strands, each about 30 bases long. These short strands fold the long strand into the smiley face shape. I call the method “scaffolded DNA origami”. (For the record: there is no fundamental significance to the fact that it is viral DNA; I could buy it and it was cheap and pure. M13 is a bacteriophage—it can make the bacteria in your intestine sick but not you! Also, I apologize to my Japanese colleagues for the name “DNA origami” which literally translated would be “DNA paper folding”—English speakers sometimes use “origami” as verb meaning just “to fold up”, similar to the way we use “pretzel” as a verb—thus “DNA origami” had the feeling of “DNA folding” even though it is an abuse of the word “origami”.)

While the smiley face shape is somewhat silly DNA artwork, it is a high technology artifact and there is serious science behind it. We hope to use the technique of DNA origami (as well as many other techniques of DNA nanotechnology) to build smaller, faster computers and many other devices.

The best way to understand how this works is to read the original article published in Nature.

There are two supplemental files associated with this paper. The first (82 pages, 6.3 megabytes) describes the design method, block diagrams for the designs, sequences for all of the designs, and includes data on control experiments. This file is likely to be of most interest. The second (9 pages, 192 kilobytes) includes diagrams for all the designs that have the full sequence written out in the diagrams. This file is useful if one wishes to check details of the design or modify them. It cannot be printed clearly and is best viewed with a PDF viewer on the screen. Please email me with your PDF viewer name and version if either of these files do not work for you.

I apologize that the MATLAB code for the design of origami structures has not been released. Unfortunately the code was in such a bad state that it proved too difficult to clean up for release. Luckily it was quickly obsolesced by much better software caDNAno, by Shawn Douglas at Harvard. We use caDNAno to design DNA origami almost every day. It features a great graphical user interface, and a large number of other scientists are developing software that interfaces with caDNAno. Thus it has really become the standard for DNA origami design. The latest version of caDNAno is recommended, but you may also be interested in a previous version, available from a repository of legacy caDNAno code.

If you are interested in DNA origami, and DNA nanotechnology in general, and want more information, please email me. I maintain a list of researchers in DNA origami, as well as lists and repositories of references which I am happy to share.

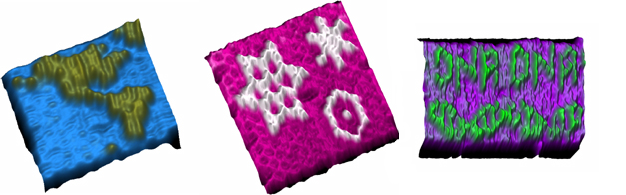

Once the basic design for a shape has been completed, one can add a surface pattern on top of the shape. For demonstration purposes in the Nature paper, the surface pattern was also made out of DNA although in principle it could be rendered using a chemically, electronically, or optically interesting material. Because each staple occurs in a unique location in the origami shape, this location can serve as a pixel. The normal DNA staple can represent a ‘0’ or a flat pixel. A modified DNA staple with an extra DNA bump (a DNA hairpin) can be used to represent a ‘1’. This is what has been done for the first three images below, the map, some snowflakes, and the word ‘DNA’ rendered above a representation of the double helix. Each of these patterns has been applied on a roughly 100 nanometer wide rectangle and each pixel is roughly 6 nanometers in size. Because there are about 200 staples, each pattern can have 200 pixels. Two copies of the origami have stuck together in the third image to make the helix appear continuous. Errors occasionally occur as in the lefthand ‘D’ in the first ‘DNA’ at right.

The structure below is a hexagon that is actually built up of six origami triangles. Each triangle has a pattern added to it (the green bumps) so that orientation of the triangles in the hexagon can be ascertained.

All of the images shown here are actual atomic force microscope (AFM) data of DNA molecules (smoothed to remove noise). An AFM measures surface topography. Here, false color is used to indicate height. The height of a basic shape (say the smileys) is just the 2 nanometer thickness of DNA. Wherever a DNA bump has been added in a pattern the surface height is 4 nanometers. The height contrast has been exaggerated (with respect to the lateral dimensions) to emphasize the topography.